Once upon a time, hoping that they might learn about colors by playing with them, the parents of young twins gave each a coloring book, “My Day at the Zoo,” and a big box of crayons. Working separately for many hours, the twins eagerly decorated the many black-outlined animal drawings in their books.

The Operator

At the end of the day, the first twin, beaming with pride, returned her finished book to her parents. She had colored the elephants a precise elephant gray, the horses in various shades of horse-brown, and the birds in many different and very bird-appropriate pastel hues. She had colored every animal picture in her book with obvious care, accurately, smoothly, and consistently, exactly within and never outside of its printed borders.

“What color is this?” the parents asked while pointing to the perfectly colored picture of a canary perched on the branch of a tree. The first twin proudly announced “Yellow!”

“And this?” the parents asked, pointing to the

To her parents’ delight, the first twin knew the proper names of every color in the crayon box, too, and even the exotic shades, like periwinkle and cerulean blue. She generalized what she had learned that day as well, correctly identifying the color of the kitchen’s new drapes as carnation pink and Dad’s necktie as puce. Her parents were very happy. As they had hoped she would, she had learned all about colors.

The Conceptualizer

A while later, the second twin returned with a scribbled-on book full of absurdly colored pictures of bright red lions and deep blue turtles. His baffled parents looked blankly at each other.

“What’s this?” asked his parents tentatively, pointing to a purple dog. “Cool huh?” replied the second twin. “I got that color by mix

“And this?” asked the parents, pointing to an orange giraffe. “That’s the color you get when you mix the red one and the yellow one,” he replied.

Perplexed, his parents fell silent. Sensing their confusion, the second twin explained, “There are lots of colors in the crayon box, but, here, see?” Using the blue and yellow crayons, he scribbled a few lines across a picture of a cow. “See?” he said again, pointing to the color he had just made. “You can make every different color in the whole box by mixing different amounts of just a few basic colors.” In response to another long, silent stare from his parents, he prompted “See? I made green! Isn’t that cool?”

But all his disappointed parents could see was a sloppily colored green cow. “Uh huh… that’s… cool...” they muttered through thin smiles, as they silently pondered enrolling him in a Special School.

Encouraging Forests to Hide Among Their Trees

As we travel along our separate paths to professional enlightenment, our journeys’ peripheral details tend to distract and even divert us. Not surprising, as, after all, aren’t we taught from childhood that great recognition and material reward bloom from the carefully cultivated seeds of knowing the littlest details? A young child, like our first twin, praised by her parents for having just learned and recited the names of the colors of all the crayons in the box, naturally sets about discovering and memorizing the names of all the other colors in her world, too. Eventually, after years of being praised for committing shade after shade to memory, the child, now all grown up, can “ace” a standardized test consisting of multiple-choice name-the-color questions, perhaps to be officially declared a Certified Color Expert (CCE). More recognition, promotion, and material reward ensue, all further proving the value of mastering even the tiniest details.

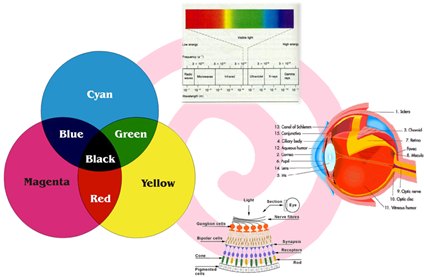

Yet, aren’t the roots of a deep awareness of the human experience of color, which had begun to sprout within the second twin, in the enlightened observation that each can be formed by mixing different amounts of the primary colors of red, green, and blue? Burnt umber’s Red/Green/Blue coordinates, for example, are 138, 51, and 36. Likewise, every hue can be expressed as numeric coordinates along these three basic dimensions, and even more profound truths underlie this knowledge, in the physiology of the human eye, and in the physics of light. Perched on the verge of these revelations, with a little encouragement, perhaps the second twin would uncover the few basic laws that govern all these many details? Will his parents find the wisdom to “color” him outside the lines of their own expectations and encourage his quest? Will he brave disappointing his parents and harness the power of his own curiosity to urge himself along in his unorthodox, but more deeply true, pursuit of understanding?

Details, we must master them, but the truth calls us from beyond them. It waits, masked, behind them. To reveal it, we must risk a deeper way of thinking. And more than merely tolerate it, we must actively encourage such thinking in others.

Questions

- We respect and reward professionals who “cross their T’s and dot their I’s,” but why settle for mastering less than 10% of the alphabet?

- We express reverence for competency. We reward it publicly. We talk endlessly of “Core Competencies” and “Competency Models” as we build our “Centers of Excellence.” But, is competency a noble enough human goal? When is competency a trap?

- As a leader, are you annoyed by people who rewrite plans, waste time on research, and meander through ideas that have nothing to do with what you expect of them? What do you risk losing when you express this annoyance?

_______________________________

Leaders with the courage to scatter seeds of creative freedom can reap a harvest of game-changing discovery. The POInT Program can help cultivate the field.

Learn more, contribute, or just follow: